The Pan African and National Cultural Heritage Tourism & Travel Project

"Continuing the ‘works’ of the Green-Book!"

"The Negro traveler's inconveniences are many and they are increasing because today so many more are traveling, individually and in groups." -Wendell P. Alston

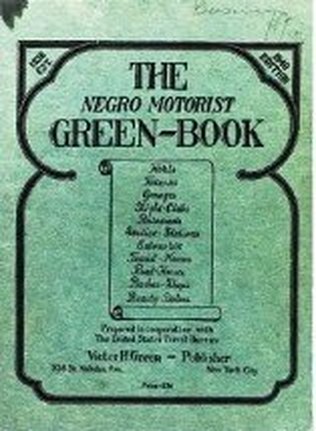

Victor Hugo Green (November 9, 1892 - aft. 1964? ) was a Harlem, New York, postal employee and civic leader. He was the creator of an African American travel guide known as The Green Book. It was first published as The Negro Motorist Green Book and later as The Negro Travelers' Green Book. The books were published from 1936 to 1964. He reviewed hotels and restaurants that did business with African Americans during the time of Jim Crow laws and racial segregation in the United States. Green used postal workers as guides to tell him: Well, here's a good place here, a good place there. And, of course, as you travel, people picked up things and told him things.

He printed 15,000 copies each year. The Negro Motorist Green Book was a publication released in 1936 that served as a guide for African-American travelers. Because of the racist conditions that existed from segregation, blacks needed a reference manual to guide them to integrated or black-friendly establishments. That’s when they turned to “The Negro Motorist Green Book: An International Travel Guide” by a Harlem postal employee and civic leader named Victor H. Green and presented by the Esso Standard Oil Company. Originally provided to serve Metropolitan New York, the book received such an alarming response, it was spread throughout the country within one year. The catch phrase was “Now we can travel without embarrassment.”

The Green Book often provided information on local tourist homes, which were private residences owned by blacks and open to travelers. It was especially helpful to blacks that traveled through sunset towns or towns that publicly stated that blacks had to leave the town by sundown or it would be cause for arrest. Also listed were hotels, barbershops, beauty salons, restaurants, garages, liquor stores, ball parks and taverns. It also provided a listing of the white-owned, black-friendly locations for accommodations and food.

The publication was free, with a 10-cent cost of shipping. As interest grew, the Green Book solicited salespersons nationwide to build its ad sales. Inside the pages of the Green Book were action photos of the various locations, along with historical and background information for the readers’ review. Although Victor Green’s initial edition only encompassed metropolitan New York, the “Green Book” soon expanded to Bermuda (white dinner jackets were recommended for gentlemen), Mexico and Canada. The 15,000 copies Green eventually printed each year were sold as a marketing tool not just to black-owned businesses but to the white marketplace, implying that it made good economic sense to take advantage of the growing affluence and mobility of African Americans. Esso stations, unusual in franchising to African Americans, were a popular place to pick one up.

Within the pages of the introduction, the guide states: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States .”

He printed 15,000 copies each year. The Negro Motorist Green Book was a publication released in 1936 that served as a guide for African-American travelers. Because of the racist conditions that existed from segregation, blacks needed a reference manual to guide them to integrated or black-friendly establishments. That’s when they turned to “The Negro Motorist Green Book: An International Travel Guide” by a Harlem postal employee and civic leader named Victor H. Green and presented by the Esso Standard Oil Company. Originally provided to serve Metropolitan New York, the book received such an alarming response, it was spread throughout the country within one year. The catch phrase was “Now we can travel without embarrassment.”

The Green Book often provided information on local tourist homes, which were private residences owned by blacks and open to travelers. It was especially helpful to blacks that traveled through sunset towns or towns that publicly stated that blacks had to leave the town by sundown or it would be cause for arrest. Also listed were hotels, barbershops, beauty salons, restaurants, garages, liquor stores, ball parks and taverns. It also provided a listing of the white-owned, black-friendly locations for accommodations and food.

The publication was free, with a 10-cent cost of shipping. As interest grew, the Green Book solicited salespersons nationwide to build its ad sales. Inside the pages of the Green Book were action photos of the various locations, along with historical and background information for the readers’ review. Although Victor Green’s initial edition only encompassed metropolitan New York, the “Green Book” soon expanded to Bermuda (white dinner jackets were recommended for gentlemen), Mexico and Canada. The 15,000 copies Green eventually printed each year were sold as a marketing tool not just to black-owned businesses but to the white marketplace, implying that it made good economic sense to take advantage of the growing affluence and mobility of African Americans. Esso stations, unusual in franchising to African Americans, were a popular place to pick one up.

Within the pages of the introduction, the guide states: “There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States .”